Trans Memory Archive

Archive

Theme: Violence against women, sexual diversities and/or for gender reasons

Address

https://archivotrans.ar/index.php (digital)

Country

Argentina

City

Continent

América

Theme: Violence against women, sexual diversities and/or for gender reasons

Purpose of Memory

To protect, build and vindicate the memory and recent history of the Argentine trans community through the recovery and protection of its documentary heritage.

Known Designation

(Es) Archivo de la Memoria Trans

Public Access

Free

Location description

The Trans Memory Archive (AMT as in its Spanish acronym) is a collaborative and independent project managed by transvestites and transgender people from Argentina that gathers images and stories about the recent history of the trans community in Argentina. It is materialized through a digital platform, a photobook and some exhibitions.

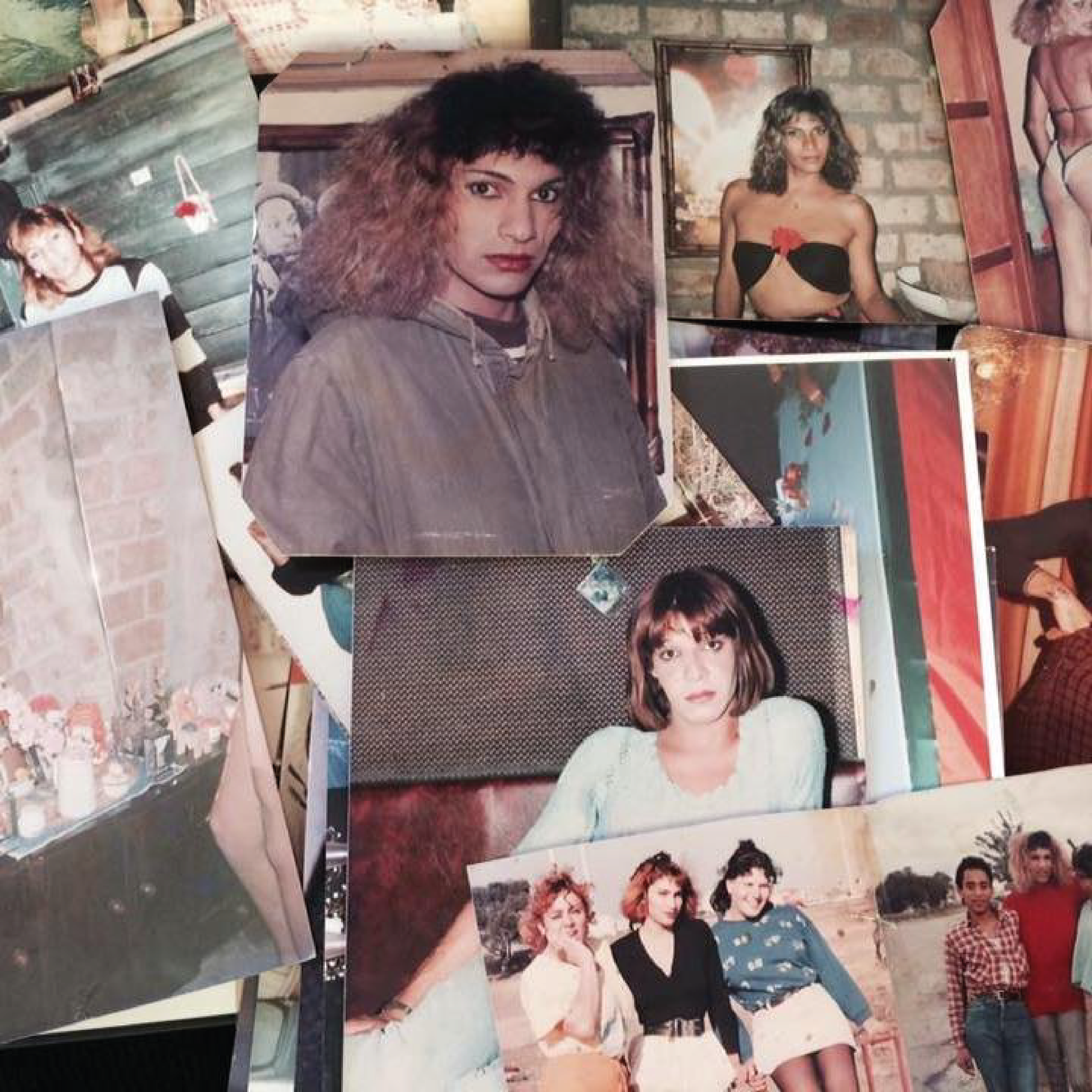

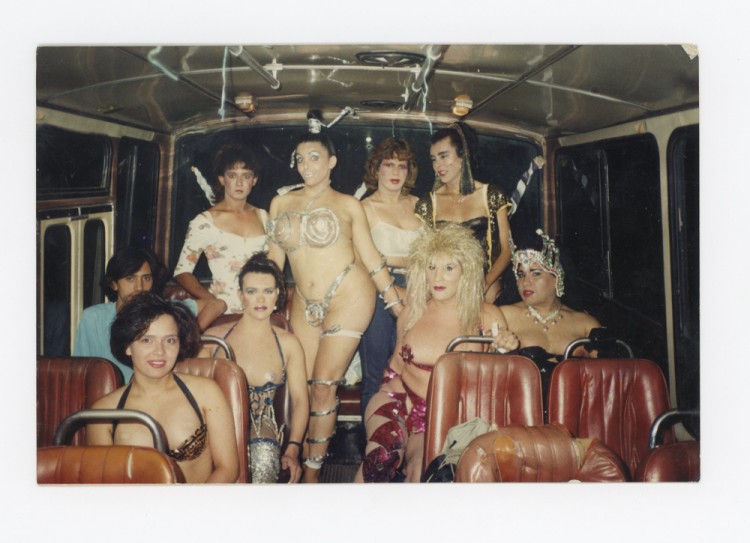

The archive currently comprises a collection of more than 15,000 pieces, including digitized analog photographs, digital photographs, videos, newspaper clippings, correspondence, personal diaries, documents -national identity documents, passports, police files-, clothing, objects and testimonies of trans people dating from the early twentieth century to the late 1990s. The oldest archival piece dates back to 1936.

The platform that virtually hosts the archive connects to the project’s social networks and is divided into seven sections: About, Catalog, Videos, Activities, Wikitrans, Publications and Press.

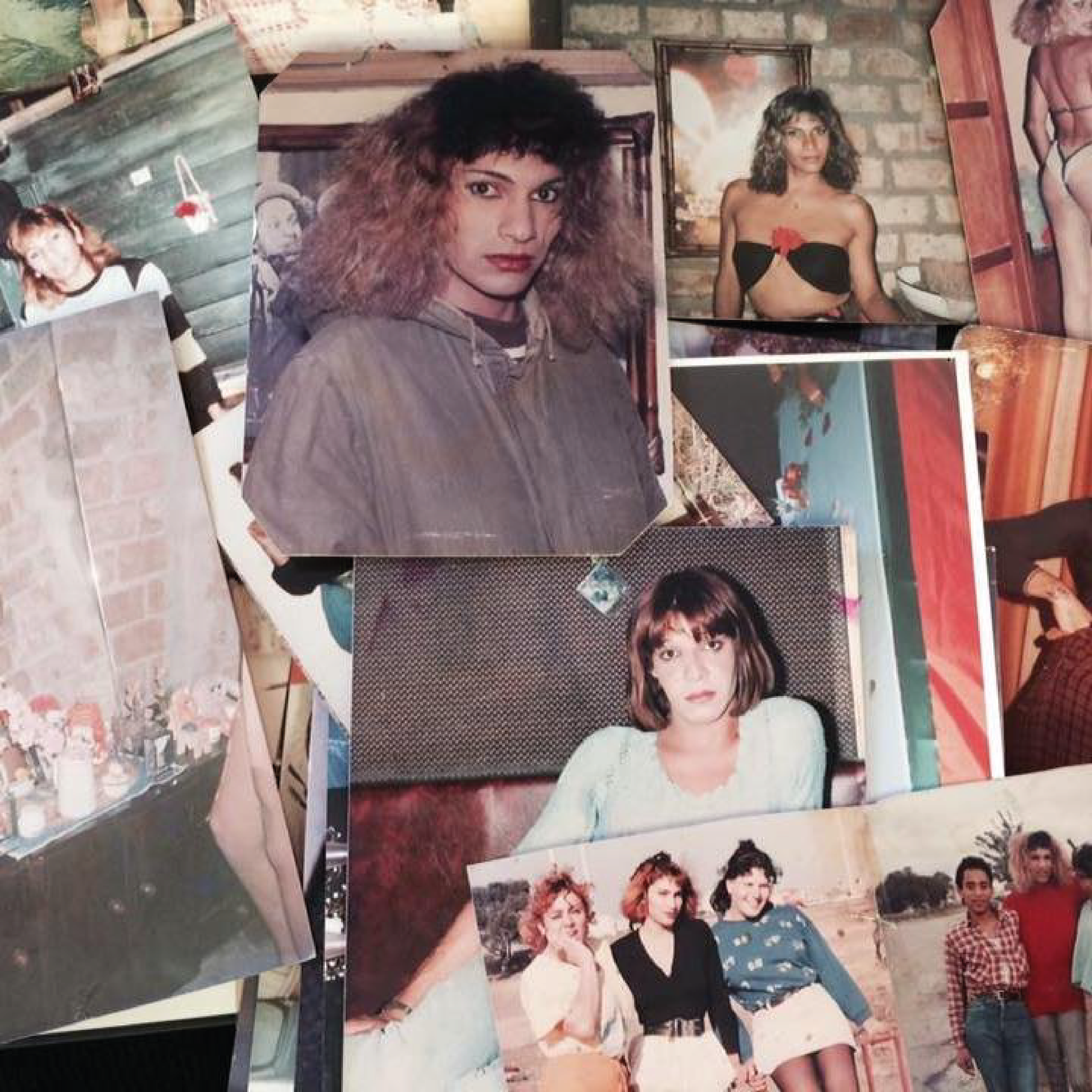

Much of this archive materialized in a book of more than 300 pages with a family album format that includes photos, postcards, documents and clippings that compile joyful moments, intimate memories and family celebrations. The book, curated and narrated by the protagonists themselves, was published by Chaco Editorial. In addition, the AMT was exhibited in several countries and spaces such as the Haroldo Conti Cultural Center in Buenos Aires, the Reina Sofía Museum in Madrid and the virtual platform of the Tate Modern Gallery in London.

Between the 1960s and the late 1990s, the transvestite and transgender community in Argentina was subjected to sustained violence. In this context, the last civil-military and ecclesiastical dictatorship in Argentina was a period of exacerbation of this violence, which sought to establish a family model and a supposedly patriarchal “Western and Christian” morality. During the dictatorship, places such as the Pozo de Banfield, a clandestine detention, kidnapping and torture center of Buenos Aires Provincial Police’s Security, Investigations and Intelligence Brigade, acted as a special corrective for sexual dissidents.

Sexual dissidences, victims of State terrorism, were historically made invisible and it is estimated that in the investigations carried out by the National Commission on the Disappearance of Persons, around 400 files catalogued under the category of “depraved and sodomites” were excluded at the request of the Catholic community. In addition, the counting of trans victims is complex because many were not sought by their relatives, were dettained with a different identity than the self-perceived and/or catalogued as NN.

Only in 2018 did the government of Santa Fe recognize 19 trans and transvestites women as political prisoners and victims of the last dictatorship due to their gender identity, and allowed their access to historical reparations through provincial law 13.298, a measure that seeks to be extended to the rest of the victims.

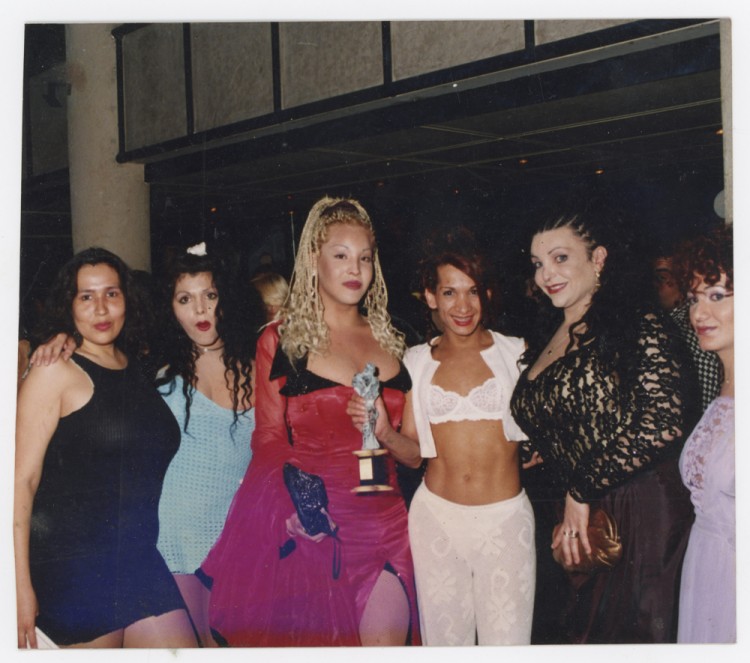

In Argentina, police edicts that ruled the illegality of trans persons and allowed them to be arrested and fined for simply walking the streets were in force until 2000. During the dictatorship, an article related to the wearing of contrary gender clothing, and in democracy until 2000 an article that alluded to public scandal and incitement to carnal intercourse, functioned as a normative framework to justify abuses and police persecution of trans identities. Being part of the community of trans women was synonymous with living in hiding, being persecuted, criminalized, discriminated against, segregated, physically and/or symbolically violated on a recurrent and daily basis. Police methods were violent and the street was a dangerous place to meet and work. The Pan-American Highway, where many transvestites/transsexuals worked as prostitutes, was a place of police persecution and murder. The visibility of the community was not possible because trans people were denounced and the strategy was to survive hidden without “coming out of the closet” (a phrase used to refer to trans people who had to hide because of the social discrimination and violence they suffered in the public sphere). This context forced the mass exile of many trans people between 1970 and 1990. In fact, the carnival and the exile during this period were meeting places for the trans community, since they were possibilities to express their identity and to move in public without being repressed.

From 1990 onwards, a series of regulatory frameworks and rights policies promoted by different social organizations of the LGTB+ collective began to change the situation of the trans community and many exiled trans women began to return to the country. In the 1990s, the first precedents of cases of trans people requesting a change of name and sex before the courts were set. On May 24, 2012, Argentina’s Gender Identity Law (Law 26,743) was enacted, allowing the depathologization and destigmatization of trans identities that until then were diagnosed as “sexual identity disorder or gender dysphoria”. This law allowed people to be treated, to modify their data in their personal documents and to be attended by the health systems to adapt their body to their self-perceived identity through hormonal therapies or surgical interventions. Since 2000, trans people are no longer considered illegal and since 2003, proposals have been presented to guarantee their right to identity and comprehensive health care, putting an end to the judicial, criminalizing and pathologizing treatments with which they were treated.

In 2018 the crime that caused the death of Diana Sacayán was the first to be categorized as a gender identity hate crime and transvesticide. Diana was a trans activist who fought for the inclusion of the transgender collective, created the Liberation Antidiscrimination Movement and promoted the trans quota law project in the province of Buenos Aires. In 2015 she was found stabbed to death with 27 injuries and signs of torture. Six years later, in 2021 the Transvestite Trans “Diana Sacayán-Lohana Berkins” Quota and Labor Inclusion Law was sanctioned, which established the reservation of a minimum of 1% of positions and vacancies in the national public sector for transvestites, transsexuals and transgender people who meet the conditions of suitability.

Despite these advances, the transvestite-trans community still suffers from discriminatory acts, physical, verbal, economic, social and institutional violence, as well as high rates of transvesticides and hate crimes. Violence, marginalization and poverty structurally violate their rights and they are not guaranteed good medical care, access to housing, education and labor insertion, which results in an average life expectancy of 35 to 40 years. From these conditions, having survived the dictatorship and also the institutional violence and structural marginalization in the years of democracy, many trans people define themselves as “survivors”.

The Trans Memory Archive (AMT by its Spanish acronym) began as a personal initiative of Claudia Pía Baudracco, who throughout her life was portraying and collecting photographs of her colleagues. Baudracco and María Belén Correa, both Argentine trans activists and founders in 1993 of the Asociación Travesti Argentina (today Asociación Travestis Transexuales Transgéneros Argentinas) wanted to have a meeting place for the trans community’s survivors of persecution and the memories of those who are no longer present.

When Baudracco died in March 2012, a few months before the enactment of the Gender Identity Law, Correa from her exile in the United States received her ashes with the collection and created a Facebook group to locate trans people around the world who had survived the period of persecution in Argentina. Within this group, which is accessed by invitation, images and stories began to circulate and virtual meetings were generated between trans friends who had lost track of each other. Over the course of two years, this virtual trans community scattered around the world met and began to build their collective memory by sharing photographs, stories, anecdotes, testimonies, letters, police reports and documents. In 2014 photographer Cecilia Estalles began collaborating by compiling and digitally preserving this archive.

Currently the AMT is a cooperative construction of trans women, artists, activists, journalists, researchers and curators. Recently and slowly, archives and testimonies of trans masculinities and non-binary people have also begun to be incorporated.

The history of the transvestite-trans community has been told from a cis and objectifying discourse by psychiatry, the morgue and the police. The AMT proposes that trans people themselves tell the story of their community by compiling a documentary archive of trans people’s life stories, an archive made up of photos and stories also written by trans people.

The archive is nourished by “collections” donated by trans people. Each collection is a set of documentary materials -objects, letters, photos, police files- of the same person, covering their entire life chronology: childhood, adolescence, school years, transition and present. The donor contacts the AMT and the team is in charge of finding and/or receiving it, digitizing it, returning it to its owner and cataloguing it. This material can be in any format: VHS, analog or digital photos, cards, postcards, letters.

Through this work carried out by the AMT, Baudracco’s collection, initially kept in a box, has now become a collection of more than 15,000 documents housed in a digital platform. The cataloguing of the material highlights the common thread and the common events that trans people go through during their lives: childhood, transition, activism, struggle, arrests, exile, friendships that become family, the freedom enabled by the carnival, parties, vacations with partners, the world of the stage, the professions and trades achieved, the rights acquired. From these curatorial criteria, the trans archive builds a memory of the rights violations suffered by the community and also a memory of its celebrations and moments of joy.

At the same time, this assemblage of scattered memories with stories that repeat themselves configure a group, a community. The AMT is perceived as a family united by the resistance to institutional violence that through the exercise of intimate and subjective memory builds its collective memory. For its members, the archive triggers a family reunion that opens to the community to complete the family photo album by recovering some of its missing pieces. This idea of family is reinforced by the strong bonds that trans people form among themselves after suffering expulsion from their families and from educational institutions, and constant discrimination by society.

In terms of the AMT members, recovering documents that were silenced by many of their families and hidden by official memories breaks the univocal meanings that power structures imprint on the history of a culturally diverse humanity. The AMT is perceived as a memory builder and a legacy at the same time. It proposes itself as a living document in constant expansion and a research platform crossed by the photographic language that recovers and articulates invisible historical documents to promote visual and political action. In fact, its members are currently demanding a comprehensive trans law that allows for reparation measures to survivors over 40 years of age.

Links of interest

Official site of the Trans Memory Archive

"Valijas" - Documentary series on the AMT

"Present" - The photos and stories of the Argentine Trans Memory Archive collected in a book

El lugar sin límites - Archivo de la Memoria Trans (Argentina) and Travesteca (Brazil)

This one is gone, this one died, this one is no more. The Trans Memory Archive in Argentina