Arpilleristas from Lo Hermida

Artistic heritage

Intangible

Theme: Political persecution

Address

Lo Hermida neighborhood, Peñalolén comune

Country

Chile

City

Santiago de Chile

Continent

America

Theme: Political persecution

Purpose of Memory

The arpilleras as a means of denunciation and resistance were originally used by women from various communities in Chile as an instrument against censorship during the last military dictatorship in the country (1973-1990), disseminating through their scenes and figures various human rights violations perpetrated by the de facto government. Since then and to this day, its representations also function as a vehicle for the dissent of its creators and Chilean civil society with various political, economic and environmental events and situations that affect citizens, communities and native peoples.

Date of creation / identification / declaration

1974

Public Access

Free

UNESCO Connection

Recognized as Living Human Treasures by UNESCO in 2012.

Location description

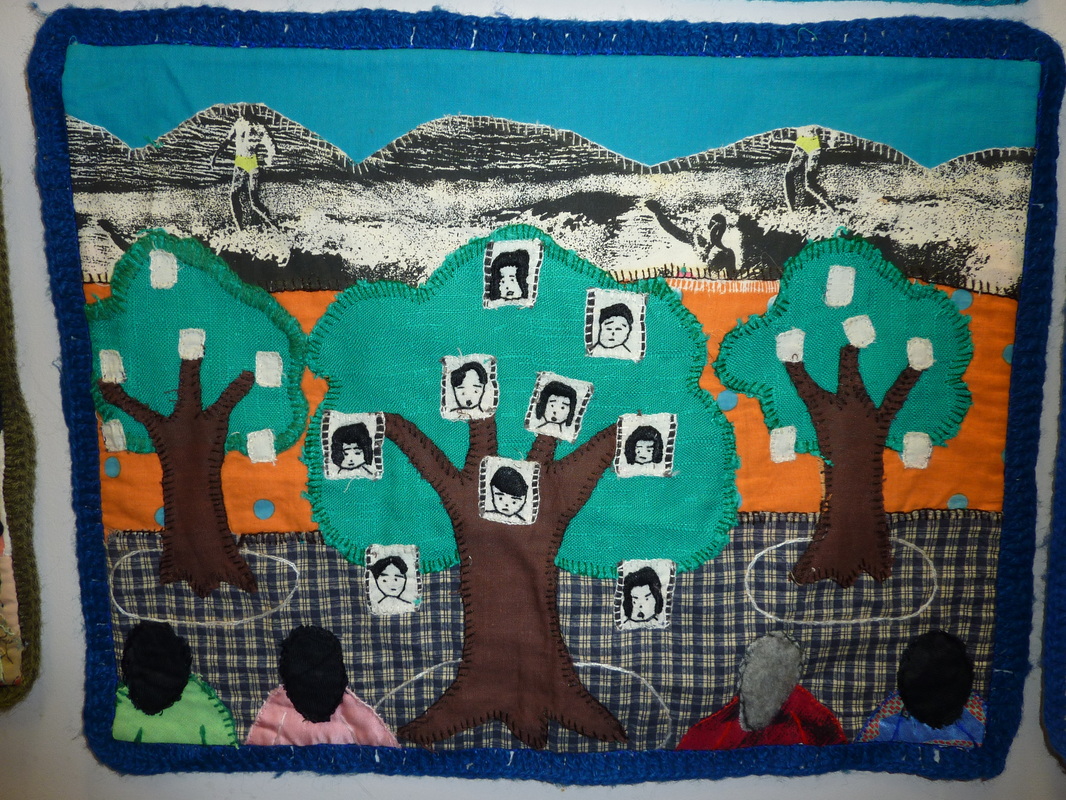

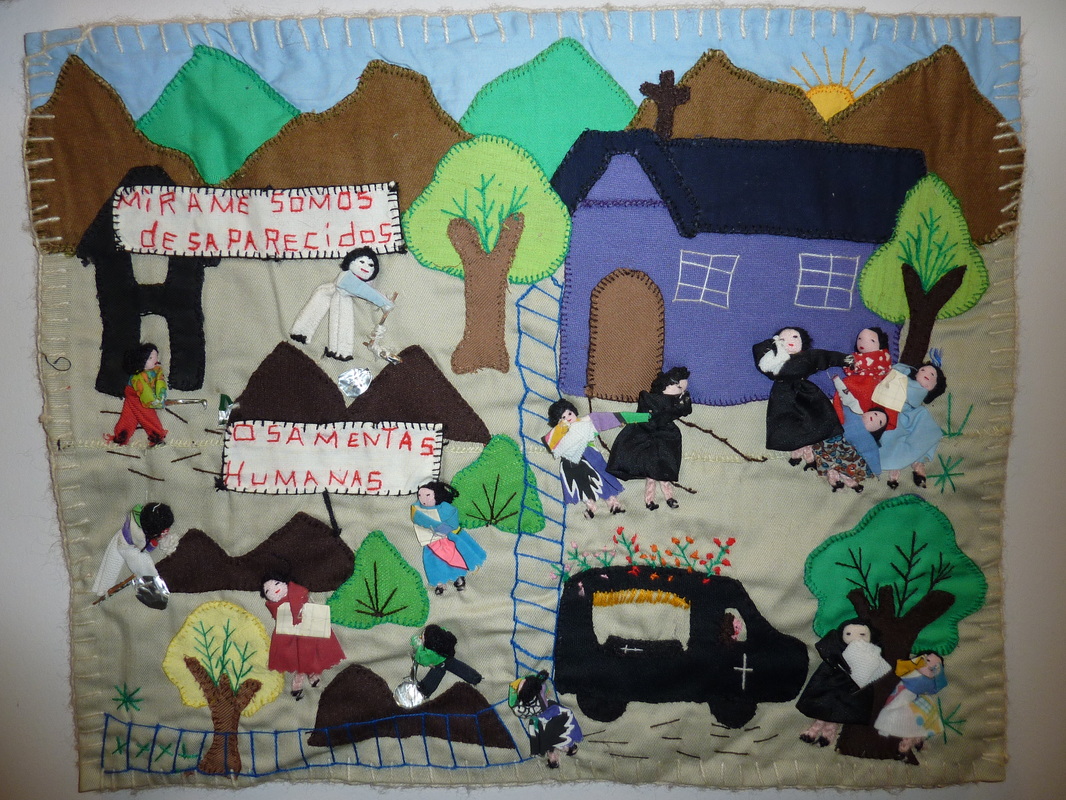

In Chile, arpilleras is the name given to both a traditional handicraft technique and the resulting works of art made from recovered or recycled materials such as cloth, copper, wool and thread, among others. Pieces and fragments of the aforementioned materials, of different colors and designs, are cut out and joined to a thicker fabric by means of various stitches embroidered with a needle, thread and wool to create an artistic textile piece or tapestry that represents scenes from the country’s political history and/or everyday experiences.

On September 11, 1973, the armed forces of the Republic of Chile revolted and carried out a coup d’état led by the Military Junta composed of Generals Augusto Pinochet Ugarte, Gustavo Leigh, César Mendoza and Admiral José Toribio Merino, commanders-in-chief of the Army, Air Force, Carabineros and Navy, respectively. At that time, the country was going through an economic crisis and an inflationary process aggravated by the economic blockade of the United States government and the consequent closing of Chilean imports to that country. The military coup leaders demanded the resignation of President Salvador Allende, leader of the Popular Action Front, who assumed the presidency on November 4, 1970 after democratic elections. Allende announced that he would not surrender and died in the bloody army attack to the Moneda Palace, seat of the executive branch of government.

After the dissolution of the National Congress, the dictatorship was led by a military junta headed by the commander-in-chief of the Army, Augusto Pinochet, who ruled under a state of emergency in which political parties were banned and social and union mobilizations were prohibited. Since 1974, the security and intelligence agencies -particularly the National Intelligence Directorate (DINA)- exercised a policy of persecution and systematic repression of any form of opposition or dissidence against the military regime.

In parallel, the de facto government proposed reforms that constituted a revision of the country’s economic policy during the last three quarters of the 20th century. The first stage of the Chilean neoliberal model, which lasted from 1974 to 1982, involved a major liberalization of imports, important reforms of the financial system and a significant opening of trade to the outside world. As a result of these measures, Chile experienced high unemployment, declining wages, the closure of numerous companies and a discouragement of investment capital formation. All of these consequences had a perceptible impact on the daily lives of thousands of people in the country, especially in poor neighborhoods and areas submerged in conditions of social and economic vulnerability.

Demands and demonstrations against the dictatorship increased, and it was not until 1988 that a referendum was called, in which the citizens voted in favor of calling for democratic elections.

On March 11, 1990, Patricio Aylwin took office, the first democratic president after the coup d’état. However, the political regime continued to be conditioned by the presence of General Pinochet, who was the head of the Chilean Armed Forces until 1998 and then, as a senator for life, still exercised some control over the Chilean army.

In April 1990, the new democratic government created the National Truth and Reconciliation Commission to investigate crimes committed during the dictatorship. The number of people detained, tortured and exiled amounted to 40,000, among whom more than 3,000 were murdered or remain missing.

The technique and production of the arpilleras and even their character as vehicles for social protest have antecedents in the previous decades of the 20th century in Chile: the embroiderer Leonor Sobrino picked up an ancient folkloric tradition to develop since 1960 the first workshops of embroidery and weaving in sackcloth with the women of Isla Negra (located in the central coast of the country), while the singer Violeta Parra exhibited her works in sackcloth, among them “Against the war”, in the Louvre Museum in 1962.

In the context of the Pinochet dictatorship, the arpilleras had in the beggining a therapeutic purpose for their makers, but ended up playing an important role both politically and as a vital source of economic support. During the first month of the Pinochet dictatorship (September 1973), Catholic, Evangelical and Jewish churches in Chile created the Committee for Cooperation for Peace in Chile (also known as the Pro-Peace Committee and as COPACHI). The goal of this entity was to assist those in need or in danger due to the new political reality, especially those most directly affected by the repression. Among other actions, the Committee provided financing and technical assistance for labor initiatives such as workshops and micro-enterprises, which helped alleviate the consequences of unemployment or the absence of the person who was usually the family’s breadwinner. Within the framework of this network of solidarity and associativity, the arpilleras workshops became one of the most transcendent experiences, a creative space where a significant collective conscience of solidarity in the face of shared injustices was developed. The COPACHI ceased to exist on December 31, 1975 due to pressures from Augusto Pinochet, although its work was taken up and deepened -including the strengthening of the work of the arpilleristas- by the Vicariate of Solidarity from the first day of 1976.

While the majority of those detained, disappeared and murdered during the dictatorship were young adult men, the social organization to visit the detainees and obtain their freedom or to find the disappeared and establish the truth was mostly the work of women. Mothers, wives, daughters and sisters led the denunciation of repression, especially through the Agrupación de Familiares de Detenidos Desaparecidos. The first arpilleras workshops began in 1974, at the request of the Committee, in charge of the artist Valentina Bone together with the Agrupación Desaparecidos. These workshops were based on the artistic tradition begun in the previous decade in Isla Negra and the designs of clothing made from overlapping fabrics by Kuna women from Panama and Colombia, and were the immediate antecedent for the emergence of the Arpilleras from Lo Hermida Workshop and many others in various areas of Santiago de Chile and other provinces. These operated for more than three decades under the aegis of the Vicariate of Solidarity and its successor, the Solidarity Foundation, and were aimed at providing economic assistance to women with the production of tapestries: most of the arpilleristas belonged to the most vulnerable and impoverished communities of Chilean society, especially affected by the economic and repressive reordering of the dictatorship. In addition to serving as a tool for economic survival and expressing in their scenes a form of denunciation of what was forbidden to be said -repression, disappearances and torture, hunger caused by unemployment, lack of access to health and education- the arpilleras had a therapeutic function, providing psychological and emotional support. Through the exercise of this technique, their creators could meet and learn about similar experiences lived by other women while externalizing lived experiences and expressing ideals in their works.

With scraps of fabric, sometimes taken from their own clothes, in these usually anonymous works the embroidery complements the stitching and reinforces the explicit narration of concrete facts. The technique is extremely versatile, relatively simple to transmit and inexpensive, given the use of recycled materials: potato sacks, threads, needles and scissors. During the dictatorship, it was common for foreign lawyers to buy the works, which circulated in Chile to a much lesser extent than outside the country. Making, owning and/or exhibiting arpilleras were considered risky activities, and the arpilleristas worked clandestinely, often at unusual times and in unusual spaces. For the military junta, the arpilleras were “defamatory mats”, “seditious crafts”, “subversive material” and “anti-Chilean propaganda”.

Patricia Hidalgo and María Madariaga are currently the only two arpilleristas who, since 1976, still carry out the work and the task of transmitting knowledge for the production of these works. Although the arrival of democracy in 1990 found them still making arpilleras for the Solidarity Foundation, in 2011 the institution closed its doors and the arpillera as a visual language and collective imaginary and as a support for political and social denunciation was at risk of disappearing. However, that same year Chile’s Museum of Memory invited Hidalgo and Madariaga to participate in a series of talks and workshops on arpillerismo, opening the way for the teaching and transmission of the technique to new generations. In 2012, the artists began to disseminate their work to different areas of Peñalolén through the Ocuparte project, promoted by the Peñalolén Cultural Corporation, holding workshops on arpilleras in many of the commune’s neighborhood councils.

The arpilleristas became agents of social change and political resistance through the use of a tool traditionally considered feminine, as a non-violent vindication of the situations they were living in the individual and collective sphere. Their works are based on a politicization of care, given that they articulate the denunciation through maternal ethics, collective action arising from the need for family sustenance, and a technique and materials associated with innocence and candor, but used in their fabrics to challenge dictatorial and patriarchal authority. From recording the atrocities of the coup d’état and denuncing human rights’ violations, over the years they’ve also added to their corpus the portrait of popular daily life during the dictatorship, a commentary on various facets of the transition and post-dictatorship periods, and the observation of some problems of present-day Chile such as the claims of indigenous peoples, student protests or mobilizations for environmental causes. Through the knowledge and practices that support the production of arpilleras, which in turn support a particular vision of the world, these artisans account for an intangible cultural heritage that has led them to be recognized as Living Human Treasures by UNESCO in 2012.

Arpillera belonging to Veronica del Negri's collection. Author: Rebecca Ansen. Source: revolutionsofsouthamerica.weebly.com.

Links of interest

Exposición | Persistir, Dignificar y Transformar: Pensar la artesanía a 50 años del golpe de Estado

Corporación de Cultura Peñalolén - Chimkowe

Retazos de Memoria. De Lo Hermida a Puerto Montt

MEMORIA ARTÍSTICA CULTURAL DE PEÑALOLÉN by Centro Cultural Chimkowe - Issuu

SIGPA - Arpilleristas de Lo Hermida

Arpilleristas de Lo Hermida | Subdirección Nacional de Patrimonio Cultural Inmaterial

Arpilleristas preparan conmemoración de los 50 años del Golpe - Artesanías de Chile

Entregaron Arpillera de la Memoria al Museo Histórico Nacional

Arpilleras que hablan. Para potenciar el proceso de… | by María Eugenia Pozo Díaz | Medium

La transformación económica chilena entre 1973-2003

¿Qué es una arpillera? | Fundació Ateneu Sant Roc

Las arpilleras, una alternativa textil femenina de participación y resistencia social

Contra la Guerra, el mensaje pacifista de Violeta Parra 50 años después - La Tercera