Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site

Site

Theme: Genocide and/or Mass Crimes

Address

55411 County Rd

Country

United States of America

City

Kiowa

Continent

America

Theme: Genocide and/or Mass Crimes

Purpose of Memory

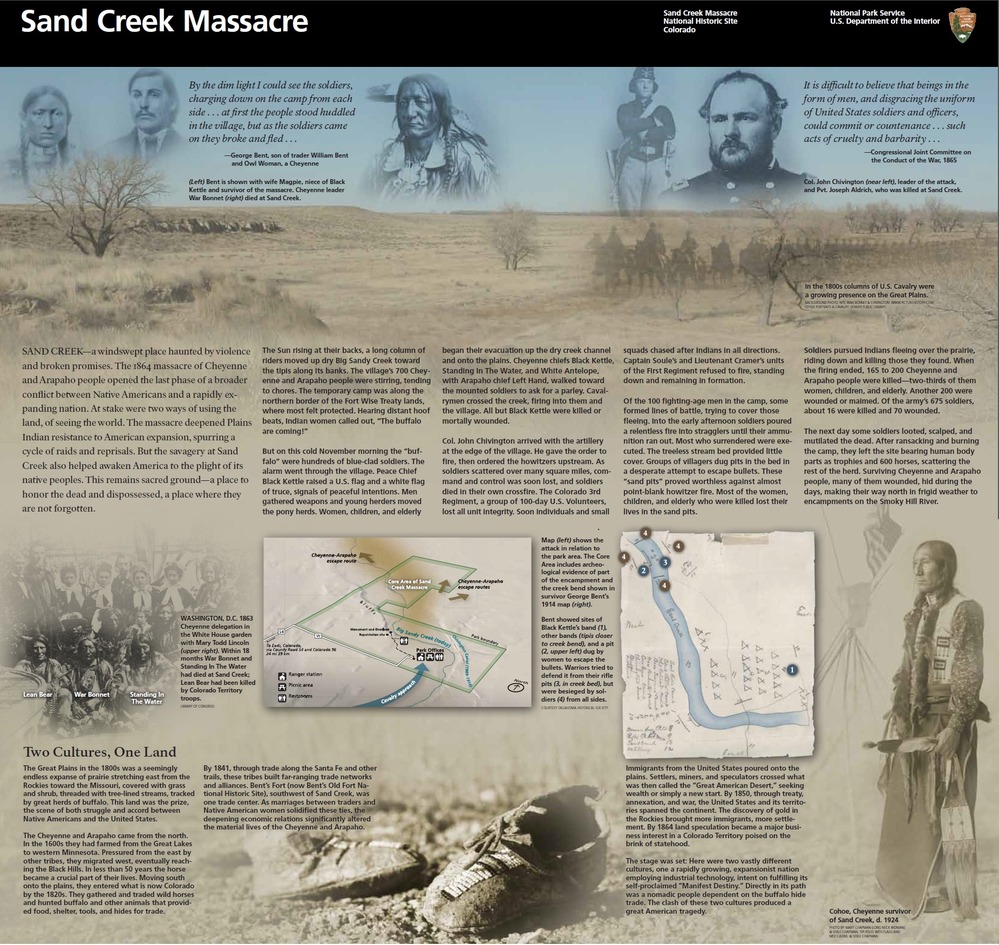

To commemorate the massacre of 1864 against members of the Cheyenne and Arapaho American Indian tribes.

Institutional Designation

Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site

Date of creation / identification / declaration

2000

Public Access

Free

Location description

The Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site is located to the east of Eads, in Colorado, United States. The site is composed by a trail that leads to a hill, where there is a commemorative monolith with the date of the events thereon. Alongside the trail, there are ten informative signs that tell the story. The Sand Creek Spiritual Healing Run is held every year, at the end of November, and covers the trail from Sand Creek to Denver; it symbolizes the route used by soldiers when coming back from killing the Cheyenne and Arapaho people in 1864.

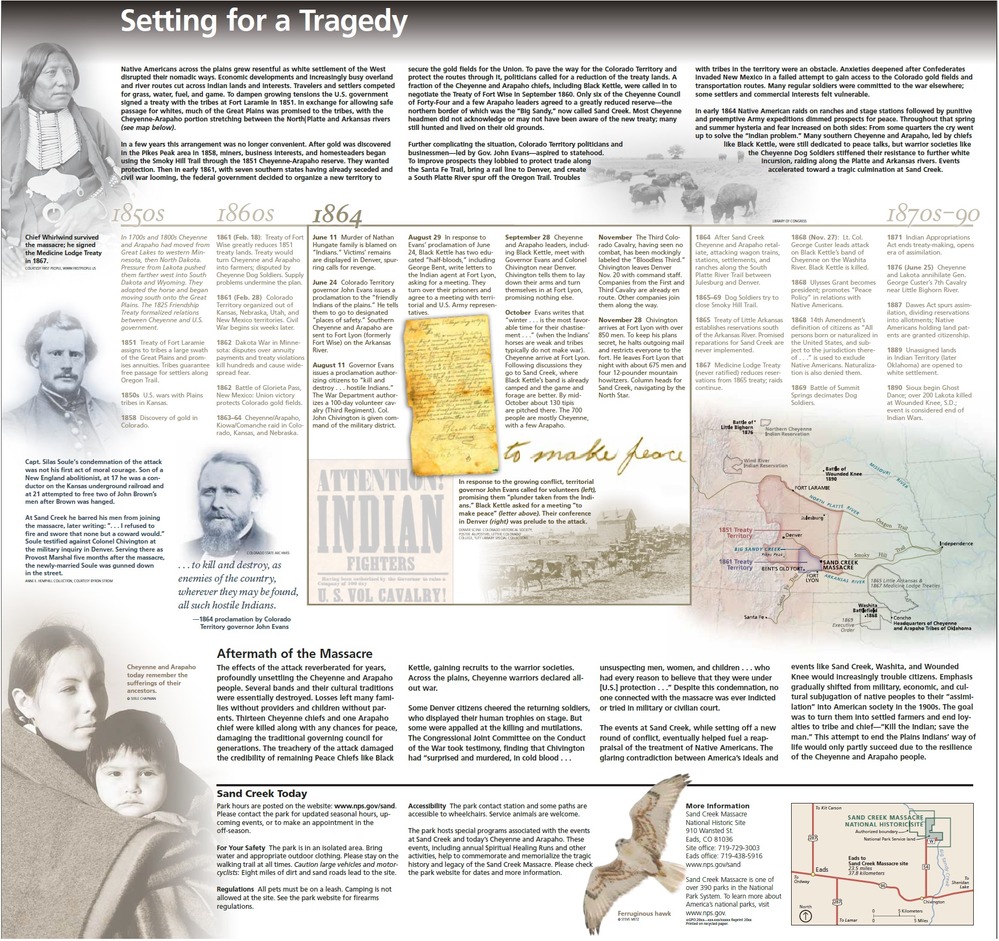

Between 1861 and 1865, United States of America fought a Civil War that emphasized the need of territorial domination by the Government. The different military invasions, in their ambition for conquest, increasingly displaced the people who had occupied those lands for centuries, and who were an obstacle for the intentions of forming a national State.

However, the need to maintain a commercial relationship with natives of those lands, the Cheyenne and Arapaho people, came before the conformation of the State. Therefore, between 1820 and 1850, a series of treaties were signed to contain the American Indian resistance, to relegate it to areas previously defined by the Government, and to get the benefits of the land, mostly gold.

The Cheyenne and Arapaho people, at first, only joined because of trade reasons. However, new settlements and the colonialist outpost started to decimate wild animals, such as buffalos, to destroy grassland needed to feed horses and to close several roads, so both tribes finally joined in peaceful co-existence.

The conflicts between the colonists and the American Indian people were more serious as new settlements stopped being sporadic and turned into permanent. In this context, suitable conditions arose for what would happen on the night of November 29 and the early morning of November 30, 1864, when the forces of the First Colorado Cavalry, commanded by Colonel John Milton Chivington, attacked a Cheyenne and Arapaho settlement in the south east of Colorado. Although weeks before, the members of these people had made public repeated calls for peace, that day, a company of the Army of about seven hundred men marched from Fort Lyon to Sand Creek to kill more than one hundred Cheyenne and Arapaho people camping there, where an American flag waved next to a white one in clear sign of no aggression.

When Chivington ordered his troops to attack, two officers (Silas Soule and Joseph Cramer, each one leading a company) refused to obey and forced their men to maintain a ceasefire. Thanks to their testimonies, the atrocities committed in Sand Creek were finally known, such as genitalia mutilation, dismemberment and stealing of sacred objects, among others. Victims were mostly women and children, since most warriors were hunting buffalos far away from the camp.

For decades, the exact location of the massacre site was not known, so many theories came up. In 1950, a first monument was erected in memory of the massacre of Cheyenne and Arapaho American Indian tribes, in a place several kilometers away from the current memorial. In 1998, a law was promoted that started with the process of localization of the Sand Creek massacre site, and therefore, a group of archeologists of the National Park Service and the Colorado Historical Society, together with Cheyenne and Arapaho descendants, started the search for the remains of the site. Senator Ben Nighthorse Campbell, the only Native American member of the Congress and Cheyenne descendant of the Massacre survivors, was the one who promoted this law.

As part of the localization effort, the descendants of both tribes told stories of the massacre that had been passed through generations. Different historical documents, such as maps, journals, and military investigation reports and Congress reports were investigated, looking for information that could provide the exact location. Also, citizens were urged to provide any information they thought useful for the exact reconstruction of the zone. There was also a geo-morphological evaluation to identify, through soil analysis, accurate geographic accidents to be able to recover pieces abandoned in 1864.

Documentation contained in the National Archives and Records Administration played a relevant role in the completion of the project. In 1868, four years after the massacre, a lieutenant of the US Army drew a map of the Great Lakes region. This archive document was essential to locate the site. Thanks to this work, and to the efforts of the rest of the organizations and citizens of the area, Sand Creek was appointed as National Historic Site in November 2000. The US Congress authorized establishing more than 5,000 hectares as Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site. On April 23, 2007, the place became the number 391 official unit of the National Parks Service of United States.

Furthermore, in 1999, an activity started that is still ongoing to this date. The Sand Creek Spiritual Healing Run covers the trail from Sand Creek to Denver (278 km) and it symbolizes the route used by soldiers when coming back from killing the Cheyenne and Arapaho people. The race is held every year, at the end of November. It starts in the Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site and goes down to the Denver downtown, where runners pause at the monument dedicated to Silas Soule, killed in 1865, and homage is paid and ceremonies are performed to commemorate the ones killed during the Sand Creek Massacre. The race is not only held in memory of victims but also seeks for spiritual healing for any person, regardless of their origin or religion.