Manzanar National Historical Site

Site

Theme: Armed conflict

Address

5001 Highway 395

Country

United States

City

Continent

America

Theme: Armed conflict

Purpose of Memory

To commemorate the people confined at the Manzanar concentration camp from 1942 to 1945.

Institutional Designation

Manzanar National Historical Site

Date of creation / identification / declaration

1969

Public Access

Free

Location description

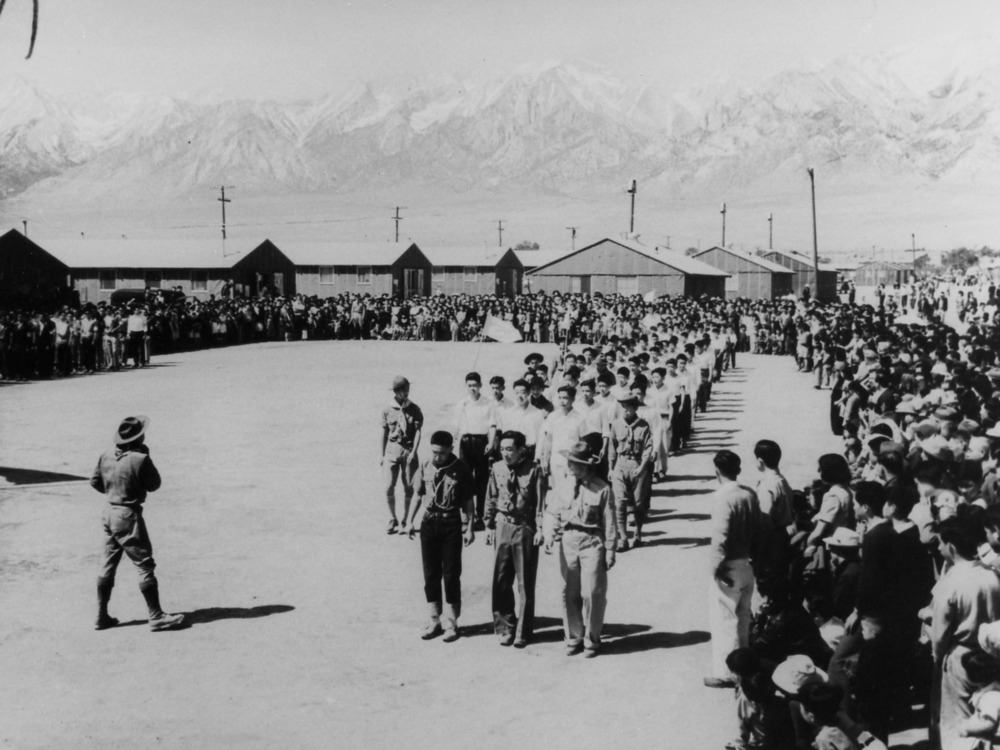

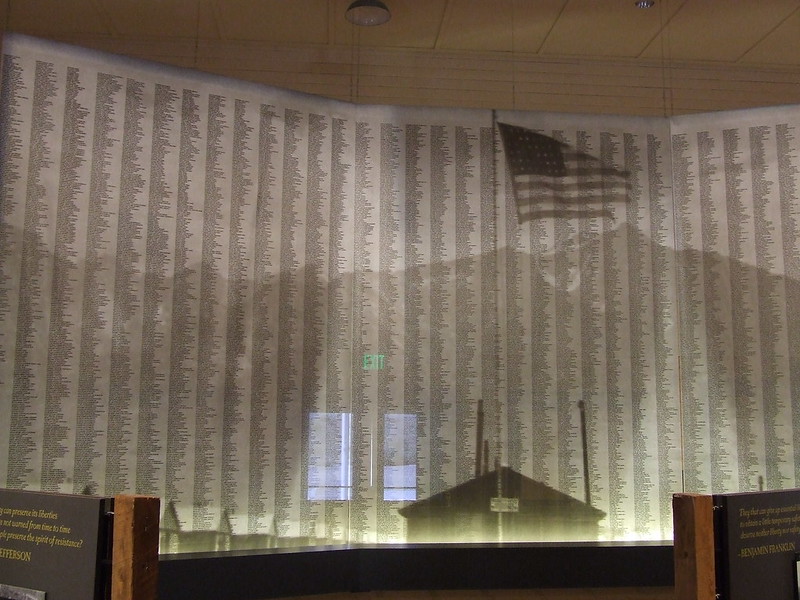

Manzanar was a concentration camp situated at the foot of Sierra Nevada Mountains (California, United States) where more than 10,000 Japanese people were detained during World War II. Today, the site features a cemetery, replica watch towers and barracks, and an interpretative center at which visitors can watch photos, objects, and reconstructed dwellings. A pilgrimage is organized every year at the site convening thousands of people, including ex-prisoners who gather at the cemetery in remembrance of their confinement. Cultural activities and an ecumenical celebration are also held at the site.

On December 7, 1941, the Japanese Imperial Navy attacked the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor precipitating the entry of the United States into World War II (1939-1945). The attack exacerbated racial discrimination against the Japanese community in the U.S. and brought about fears of potential Japanese sabotage or espionage within the U.S. Government, Army, media, and population.

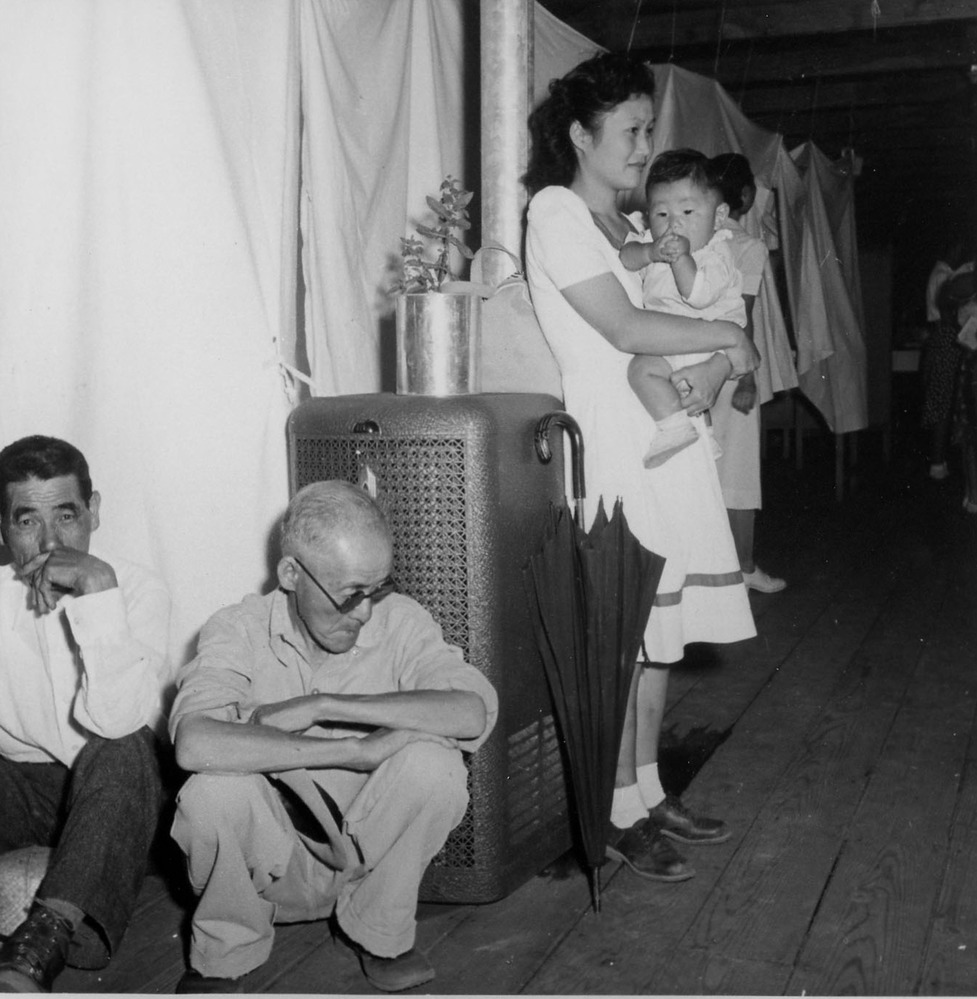

In February 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, leading to the mass incarceration of Japanese people and their descendants. Japanese residents of the U.S. West Coast were forced to abandon their homes and, with no clue about their fate, had to work out what to do with their belongings within a short time. Most of them sold their properties at a substantial loss; others rented their homes to neighbors or left them to friends or religious communities, while others simply abandoned their homes. Each family would be given an ID number and taken by car, bus, truck and train, just holding what they could carry on with them. Under military surveillance, these people were transferred to 17 temporary reception centers, situated in race tracks, fairgrounds, and similar facilities in Washington, Oregon, California and Arizona. Afterwards, they were taken to 10 “relocation centers” built hurriedly. By November 1942 the full relocation had been completed.

In March 1942, some Japanese community volunteers started to build the camp at the Manzanar site. By July, 10,000 people were already living in the 36 blocks. The Manzanar site extended over an area of 25 Km2, fenced with barbed wire and surrounded by eight watch towers. It is estimated that two thirds of the people confined there had been born in the United States.

Afterwards, ten “war relocation centers” were built in isolated areas of Arkansas, Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Utah and Wyoming. The concentration camps were arranged in such manner as to be self-sufficient, including cooperatives, animal farms and vegetable gardens.

On November 21, 1945, ten days after the end of the war, the military authorities closed Manzanar and dismantled the camp, and internees had to find relocation on their own. The impacts of this trauma based on racial discrimination gave rise to a culture of silence which extended over several generations of Japanese Americans.

In 1988, then-U.S. President Ronald Reagan publicly apologized for the confinement of 120,000 Japanese Americans during World War II and authorized a payment to compensate survivors.

In 1969, the Sansei community–a Japanese and English term used to designate the third generation of Japanese Americans– organized a pilgrimage from the city of Los Angeles to the former concentration camp at Manzanar. Pilgrims cleaned up the cemetery and arranged the obelisk built in 1943 and known as the “Soul Consoling Tower.” These sites were some of the last physical traces of the original concentration camp. That event prompted the creation of the Manzanar Committee, which is tasked with arranging the pilgrimage on the last Saturday of April every year, which convenes thousands of people, including ex-prisoners who gather at the cemetery to commemorate their confinement. The event also includes prayers, cultural activities and an interreligious service. Since 1997, the Manzanar at Dusk program has been made part of the pilgrimage seeking to attract local residents, in particular, descendants of the Manzanar area residents who were displaced during the first half of the 20th Century. Since 2001, the ceremonies have also attracted Muslim Americans looking to foster the protection of their civil rights, as distrust towards such community has been rising ever since the September 11 attacks.

Since its foundation, the Manzanar Committee has sought to recognize and protect the Manzanar site. In 1972, the State of California declared the site a historical monument. Then, Manzanar was registered as a national historical monument (1985) and as a national historical site (1992).

In recent years, an interpretative center was built in the former school auditorium, as well as a replica watch tower. The National Park Service workers usually collect origami strings and personal objects which are placed on top of the obelisk situated in the cemetery. Today, the site offers materials, programs and visits for schools.

After the end of World War II, several discussions and conflicts arose concerning the terms that should be used to refer to the Manzanar and other sites. Manzanar has been described as a “war relocation center,” “relocation camp,” “internment camp,” and “concentration camp.” The term “concentration camp” finally prevailed in 1998, based on new discussions brought about after an exhibition on American camps during World War II at the Ellis Island museum (New York).