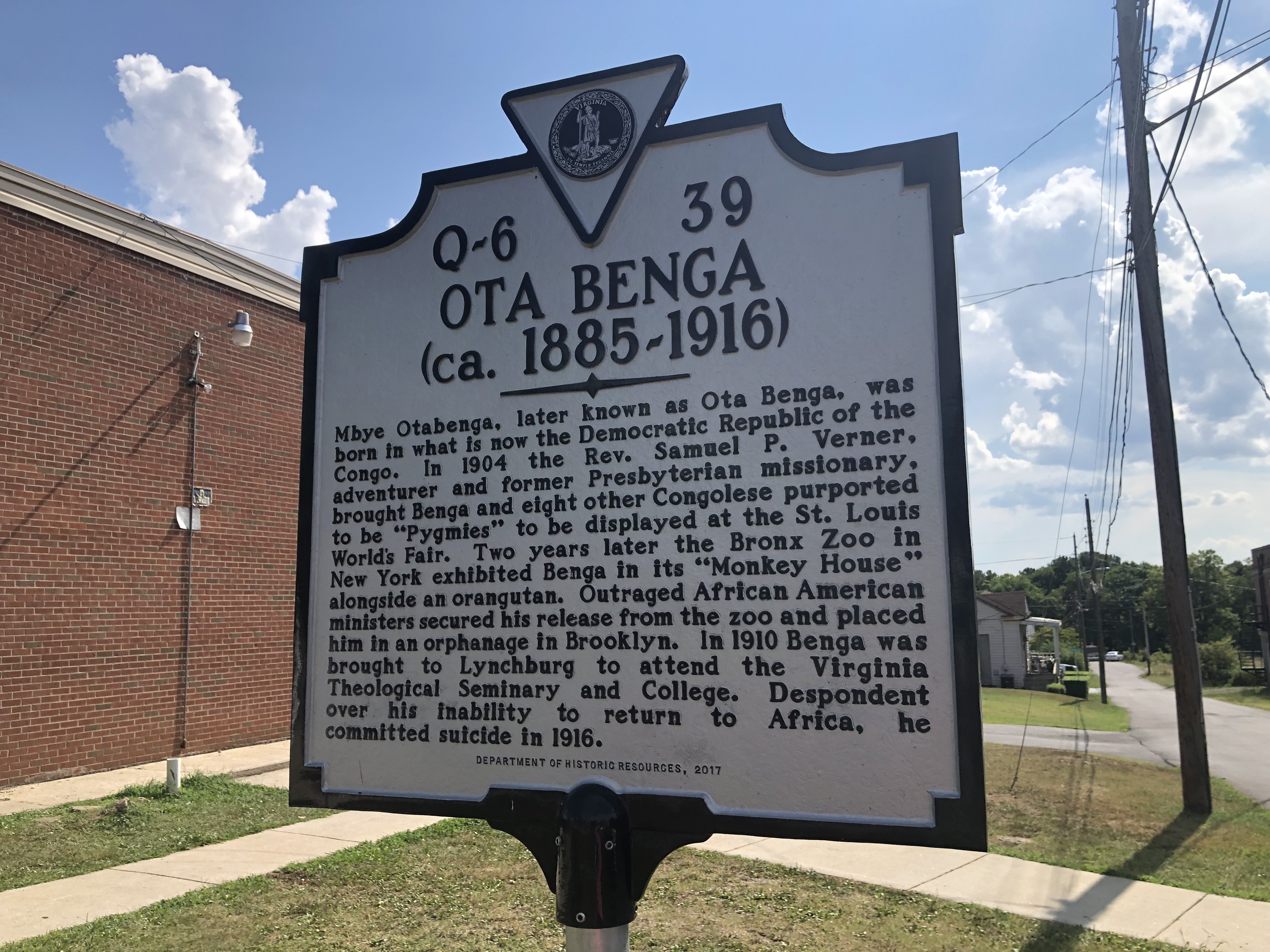

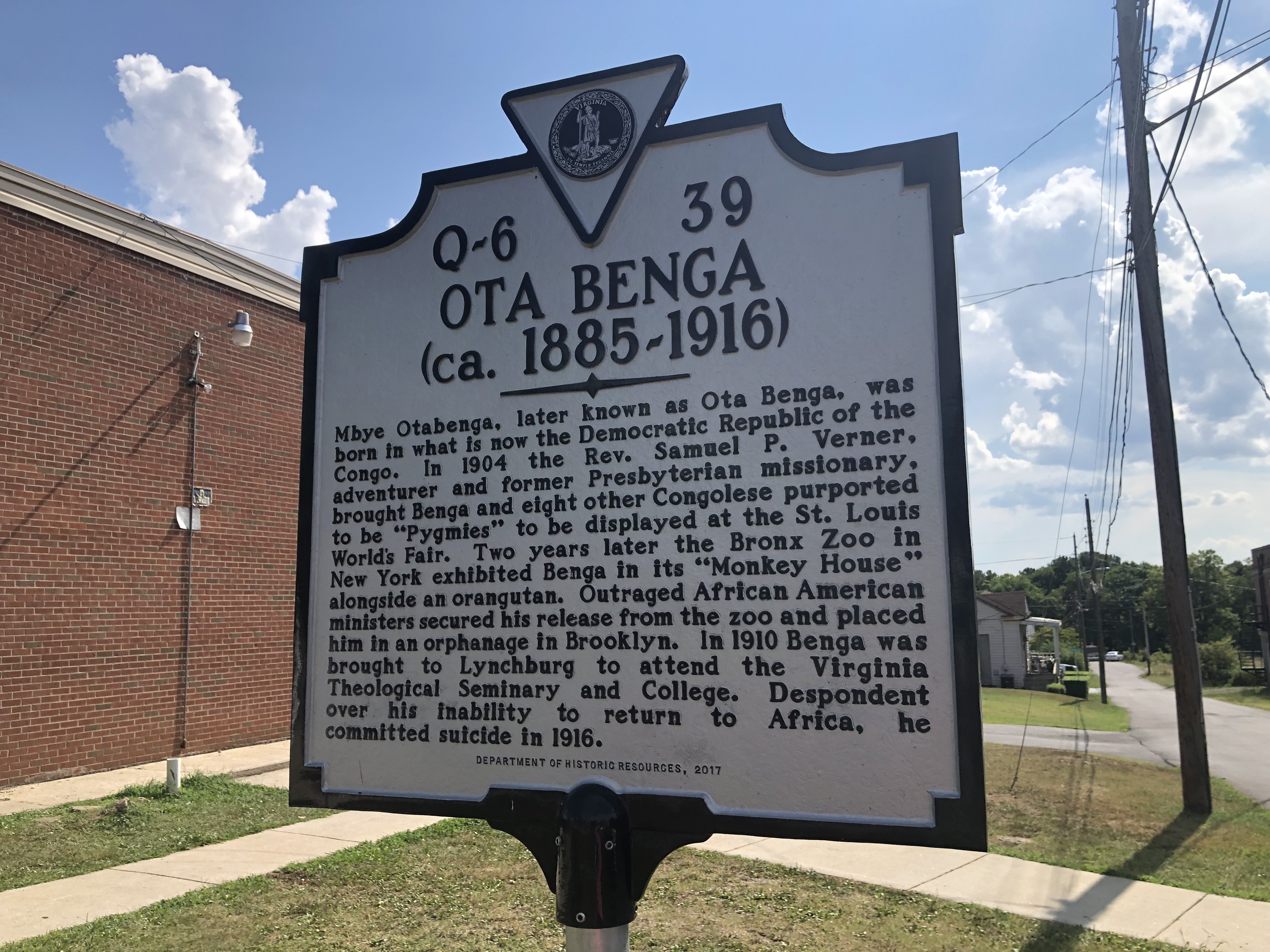

Historical marker in honor of Ota Benga

Site

Theme: Slavery

Address

2202 Garfield Ave

Country

United States

City

Lynchburg

Continent

America

Theme: Slavery

Purpose of Memory

To honor the life of Ota Benga as a person and symbol of the exploitation suffered by Africans on the hands of the world powers during the process of colonialism, and of the racial theories promoted by the sciences developed in those nations.

Institutional Designation

Historical marker in honor of Ota Benga

Public Access

Free

Location description

The site consists of a rectangular plaque with an inscription reading “Ota Benga (ca 1885-1916). Mbye Otabenga, better known as Ota Benga, was born in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo. In 1904, the Reverend Samuel P. Verner, an adventurer and former Presbyterian missionary, transported Benga and eight other supposedly ‘pygmy’ Congolese to the United States to be exhibited at the Saint Louis World’s Fair. Two years later, the Bronx Zoo in New York exhibited Benga in its ‘Monkey House’ alongside an orangutan. Outraged African-American herders managed to get him removed from the zoo and put him up in an orphanage in Brooklyn. In 1910, Benga was transferred to Lynchburg to attend Virginia College and Theological Seminary. Depressed at not being able to return to Africa, he committed suicide in 1916.”

The plaque is located near the home of Rev. Gregory Willis Hayes, president of the Virginia Theological Seminary and an advocate for African Americans whose families sheltered Ota Benga; and across the street from the present-day University of Virginia, formerly the site of the Theological Seminary. It is part of a historic corridor dedicated to Gregory W. Hayes and other historical figures who championed the rights of African-Americans in that locality.

Between 1885 and 1908, Leopold II of Belgium, king and owner of the Congo Free State, forged a fortune based on the exploitation of rubber and ivory through a regime of forced labor and insurgents’ repression by the “Force Publique”, a group of soldiers who murdered and tortured millions of Congolese at the behest of the monarch. In this context Samuel Phillips Verner, a former Presbyterian missionary and American entrepreneur, was sent to the Congo financed by the Universal Exposition of Saint Louis (1904) to search for “pygmies” and “anthropological specimens”. During his trip, Verner bought nine “pygmies” from human traffickers, including Ota Benga, a member of the Batwa ethnic group, whose Mbuti tribe – including his wife and children – had been exterminated by the “Force Publique”. Verner exchanged Benga for a pound of salt and a roll of cloth, and claimed that he had rescued him from a group of cannibals.

“Human zoos” were an epiphenomenon of colonial imperialism that found its greatest acceptance between the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in Europe and the United States. In them, people considered exotic and “inferior” by the social and scientific standards of the time were exhibited as objects of fair or spectacle. It is estimated that 30,000 people recruited from different parts of the world were exhibited in these places, especially the so-called pygmies who were considered the last step of human evolution. In 1897, for the Brussels Exposition, Leopold II had brought 267 Congolese to represent their way of life and rites to European spectators. In 1904, the Universal Exposition of St. Louis was held where Ota Benga was exhibited, without any care or shelter, together with other Congolese people, Ainu people from Japan, Patagonians, Filipinos and the Apache chief “Geronimo”. Inside the Exposition, Ota Benga was conspicuous for being less than five feet tall and having his teeth ritually sharpened. At the end of the Exposition, Verner took Ota Benga back to Africa, where he remarried. However, upon his second widowhood, Ota Benga returned with Verner to the United States and was taken temporarily to the American Museum of Natural History in Manhattan, where his bust was cast and displayed as a specimen of a living savage.

In 1906 Ota Benga was taken to the Bronx Zoo where he was exhibited in the “Monkey House” as part of a show on human evolution, alongside an orangutan named Dohong whom he took a liking to. His cage was decorated with bones to allude to his supposedly “cannibalistic” nature and he had a bow and arrow in it. He was advertised as “the missing link” and received a huge number of visitors who made fun of him and made comments. Its exhibition generated huge profits and was sponsored by Madison Grant, a racist scientist and advocate of eugenics, a theory that encouraged the manipulation of reproductive practices in order to prioritize certain phenotypic traits.

This situation took place 40 years after the abolition of slavery in the USA and provoked protests from the local Afro-descendant community, thanks to which Benga was allowed to walk around the zoo and even feed the animals. However, this caused more impact and the first day Benga was out of his cage the zoo received 40,000 visitors. His defensive behaviors in the face of visitor harassment were interpreted as violent and increased his reputation as a “savage”.

In 1906, after 20 days of residence at the zoo, Benga’s exhibit was closed due to protests by the African American community, including prominent members of the Church. Ota Benga went into the care of the Reverend James H. Gordon, who gave him sanctuary in his colored orphanage in Brooklyn for three years. In 1910 Ota Benga was taken to Lynchburg (Virginia), where he was dressed in European clothes, his sharp teeth were covered, and he attended formal instruction and the Virginia Theological Seminary. There he befriended its president Gregory W. Hayes, Hayes’ family, and poet Anne Spencer, all of whom had participated in protests against his exhibition. Ota Benga began working in a tobacco factory where he also made friends who called him Bingo and with whom he went hunting in his spare time. He had begun to save to pay for his return to Africa but the war prevented him from doing so. On March 20, 1916, at the age of 32, Ota Benga pulled out his dental implants, prepared a fire around which he danced and finally shot himself in the heart.

Ota Benga’s death had a great impact on the community, especially artists, academics and activists. His story inspired multiple books, films and songs. In 1992 Phillips Verner Bradford published the book “Ota Benga: The Pygmy at the Zoo”; in 2002 Alfeu França released the film “Ota Benga; A Pygmy in America”; and in 2015 Pamela Newkirk published the book “Spectacle: the Amazing Life of Ota Benga”. Meanwhile, African history professor Jacques Depelchin founded the Ota Benga International Alliance for Peace in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Congolese scholar Dibinga wa Said organized an international conference on Benga and the hunter-gatherers of Central Africa in Lynchburg in 2007.

On September 16, 2017, a plaque was placed in the neighborhood where Ota Benga took his life near the home of Reverend Gregory Willis Hayes, president of Virginia Theological Seminary and an advocate for African Americans whose family sheltered Ota Benga. The ceremony was attended by more than 50 people and various personalities who supported the memorial service. Among them were François Nkuna Balumuene, ambassador of the Democratic Republic of the Congo; Joan Foster, mayor of Lynchburg; Ann Van de Graaf, artist, human rights activist and director of the African House of Lynchburg; Pamela Newkirk, Benga’s biographer; and Dibinga wa Said, a Congolese academic. The ceremony featured music, prayers, displays and a book signing by Pamela Newkirk. On the same day as the ceremony, September 16 was established as Ota Benga’s day of remembrance. Also, not knowing with certainty Benga’s burial place, the community began to consider that site as a place of pilgrimage.

From historical records, it is known that on March 22, 1916, the African American church arranged Ota Benga’s funeral and gave him burial in the black section of Lynchburg’s Old City Cemetery. However, there are oral accounts that Ota Benga’s body was moved to Lynchburg’s White Rock Cemetery. Despite the uncertainty regarding the location of his burial, a second memorial has been held where his remains are believed to rest, the Old City Cemetery. This second memorial was in part a response by the citizens of the Commonwealth of Virginia to attempts by white supremacists to tear down the monuments of those who fought for the South in the Civil War. In 2021, representatives of the Congolese National Assembly Christelle Vuaga and Mme. Laetitia Basondwa visited the site and spoke to him in his native language.

In July 2020, following repudiations of the racism that led to the murder of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, the Wildlife Conservation Society in charge of the Bronx Zoo publicly apologized to the Mbuti people for the treatment of Ota Benga.