Napalpí Memorial Historic Site

Site

Theme: Genocide and/or Mass Crimes

Address

Colonia Agrícola Aborigen Chaco

Country

Argentina

City

Colonia Agrícola Aborigen Chaco, Machagai department, Chaco

Continent

America

Theme: Genocide and/or Mass Crimes

Purpose of Memory

To commemorate the victims of the Napalpí Massacre and recognize the nature of crimes against humanity in the context of a process of genocide of the events that took place there, in addition to vindicating the struggle of the native peoples in the defense of their territory.

Institutional Designation

Napalpí Memorial Historical Site

Date of creation / identification / declaration

2020

Public Access

Free

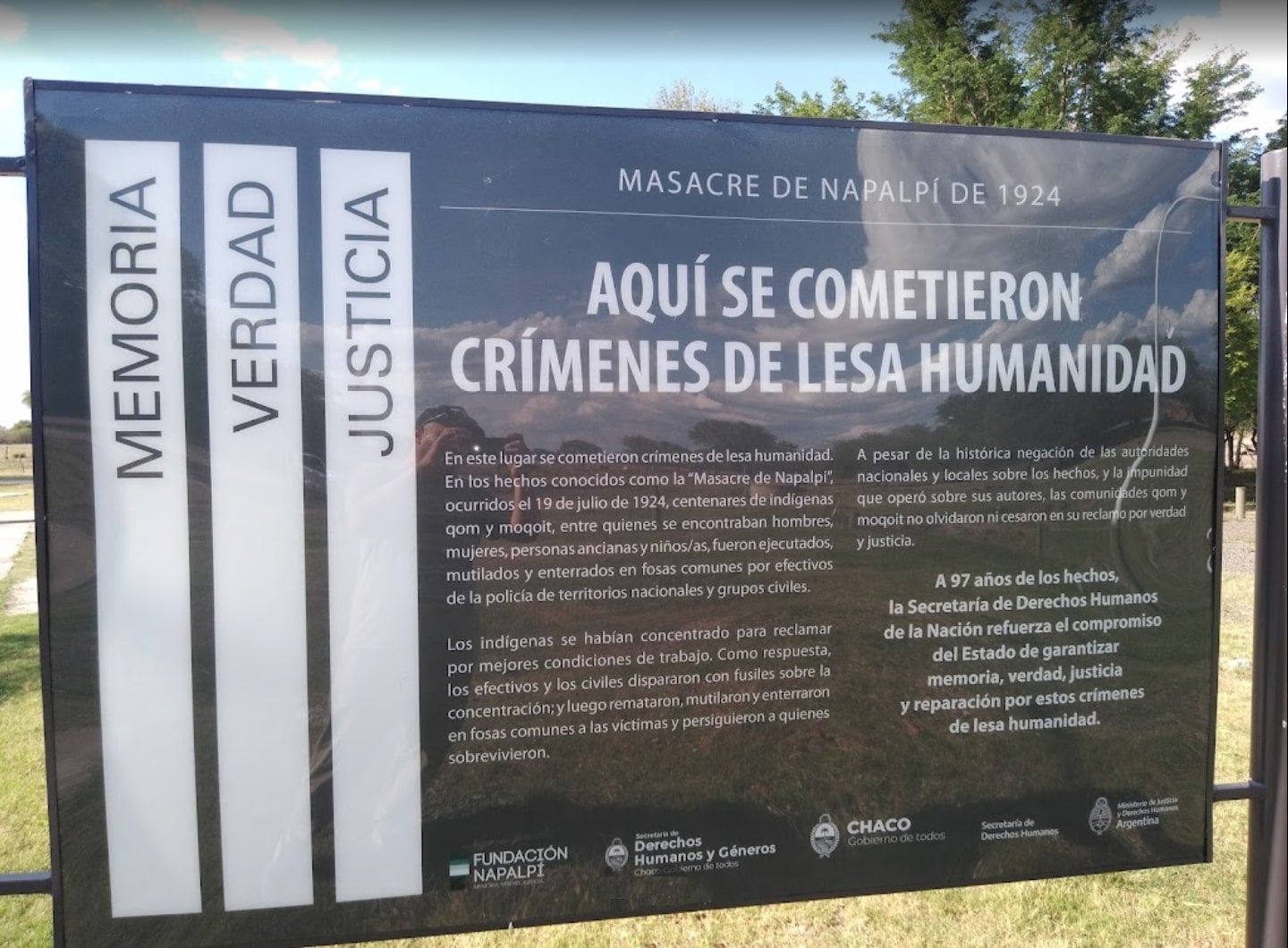

Location description

The site consists of a circular lawn space bordered by a concrete pedestrian walkway, containing within it a concrete circle at its center. Inside the circular space, four trees are planted in each quadrant, and outside the pedestrian path five trees with their trunks cut and painted orange are located on each side, each one containing an urn with the remains of a victim of the massacre (except for one belonging to a Malvinas combatant), all of them belonging to the Qom people. Next to the trunks there is a life-size crucifix and two murals with paintings and allusive phrases in the Qom language. At the beginning of the pedestrian entrance to the site there is a commemorative plaque placed by the Secretary of Human Rights of Argentina, the provincial government of Chaco and the Napalpí Foundation.

In 1884, the Argentine Minister of War and Navy, Benjamín Victorica, commanded his troops in the conquest and occupation of the current territories of the province of Chaco, then inhabited by the Mocoít, Qom, Pilagás, Wichís, Vilelas and other peoples. The process of forced displacement and their use as cheap labor required the creation of the so-called civil reductions, state institutions that delimited territories where the original inhabitants could be confined for their control and availability. The Napalpí reduction was created in 1911, on an area of 20,000 hectares. In 1915, 1300 people belonging to the Qom, Mocoít and Shinpi’ communities lived there, usually employed in the forest and cotton exploitation administered by the National Territory of Chaco in control of the territory, as well as by external settlers in their farms and sugar mills. The inhabitants of the reduction were not allowed to move freely and suffered from terrible housing, sanitary, food and working conditions, with unequal pay, without rest and forced to follow customs alien to their tradition and ancestral way of life.

Between the end of 1923 and the beginning of 1924, conflicts over these conditions between the inhabitants of the reduction and the government of the National Territory of Chaco increased when Governor Fernando Centeno prohibited the departure of indigenous people from the reduction, since the local settlers were opposed to the transfer of the labor force to the sugar mills in the provinces of Jujuy and Salta. While the Qom and Mocoit wanted to work in the sugarcane harvest, where the pay was scarce but higher than in the reduction, the settlers wanted to use them for their cotton crops. Led by the chieftains Gómez, Maidana, Machado and Dominga, hundreds of Qom and Mocoít withdrew from the reduction and gathered in El Aguará to start a strike and request for better living conditions, which was not answered at first by the authorities. In May 1924 the negotiations were extended with petitions and promises from the administration of the territory, although in the face of their non-compliance the concentration remained firm while the local press spoke of “indigenous threat” and “uprising”. In June of that year a police contingent was installed near the reduction to pursue its inhabitants.

On July 19, the Chaco II plane of the Aero Club Chaco flew over the area and dropped food and sweets from the air to drive the Qom and Mocoít out of their homes: when this happened a force of more than one hundred men of the National Police of Territories, together with settlers and landowners, fired more than 5000 bullets at the men, elderly, women and children concentrated there. Those who were not killed in the shooting were shot with machetes, beaten and tortured. Testimonies of mutilations, decapitations, impalements, burials in mass graves and incineration of corpses are preserved. The bodies of the leaders were exhibited as an example, and a jar with the ears and testicles of the chieftain Maidana remained after the massacre in the police station of the nearby town of Quitilipi. The survivors of the massacre (around forty children and fifteen adults) were hunted down until September to eliminate the possibility of witnesses. It is estimated that between 400 and 500 Qom and Mocoit people were killed in the events.

Shortly after the massacre, the first news began to circulate in the Chaco press and military reports which, in a concealment maneuver, adopted the official version that spoke of “malones” and confrontations between factions of native peoples. The federal court of Resistencia, capital of Chaco, labeled file 910/24 as “Indigenous uprising in the Reduction of Napalpí”, gathering only police versions and without witnesses from the affected communities. Centeno was forced to go to the capital Buenos Aires, where the newspapers were already reporting versions of the massacre, to expose a false version indicating that there had been four dead, all of them “Indians who killed each other”. On August 29, forty days after the massacre, the former director of the Reduction of Napalpí, Enrique Lynch Arribálzaga, denounced by means of a letter to the National Congress that the persecution of survivors continued so that they could not serve as witnesses if an Investigating Commission of the Chamber of Deputies was sent.

The case escalated to such an extent that in September 1924 the Chamber of Deputies began to discuss it with one session per week during the following month. Several legislators demanded Centeno’s resignation and the socialist block assumed the responsibility of the investigating commission. On September 4, an extraordinary session was called to question the Minister of the Interior, Vicente Gallo, for six hours. There, Congressman Francisco Pérez Leirós presented the results, referring to them as “a series of facts that seem to belong to the nightmare of a madman” and showed the jar with the ears and testicles of the chieftain Maidana.

Despite the evidence and the results of the investigations, the case was quickly closed. Centeno continued in his position and displaced the judge who was in charge of the case, Justo Farías, to replace him with Juan Sessarego, a man he trusted. The prosecutor Jerónimo Cello, who asked for the case not to be closed, was therefore removed. Sessarego acquitted the eighty police officers charged. The crime thus remained unpunished and hidden for eight decades.

In 2004, eighty years after the massacre, the organizations representing the native peoples of the Chaco initiated a civil action for compensation for damages, and in January 2008 the government of that province made a public and official apology for the events. In 2014, the National Public Prosecutor’s Office initiated a new investigation of the crimes committed in Napalpí that lasted four years to determine whether crimes against humanity had taken place, and requested the opening of a Trial for the Truth given the situation that all those responsible were already deceased. As part of this investigation, the Human Rights Unit of Chaco’s Federal Prosecutor’s Office and the civil organization Napalpí Foundation also requested the intervention of the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team (EAAF). This team began the work of exhumation of the mass grave at the site of the massacre in 2018, and found in September of the following year the first skeletal remains that determined the existence of four mass graves.

The advanced state of the investigations of the Public Prosecutor’s Office, the findings of the EAAF, the testimonies of the survivors Rosa Grilo and Pedro Balquinta and the pioneering research of the teacher, historian and researcher Juan Chico (creator of the Napalpí Foundation and author of “The Voices of Napalpí”, a book that opened to society the history of the massacre in 2008) influenced Chaco’s government to inaugurate the memorial at the current site of the Napalpí Massacre Historic Site on July 19, 2020, on the 96th anniversary of the events. During the inauguration of the site, Governor Jorge Capitanich, together with members of the Qom and Mocoít communities, placed the urns containing the remains of nine victims recovered from a museum in the city of La Plata, and a tenth urn representing former Malvinas combatants from the communities. The construction of the memorial responded to the commitment assumed by the Institute of Culture together with the Napalpí Foundation and its project of the same was carried out by Alexander Fernández, a Qom student of Architecture, who took elements of the community’s culture to design it.

On July 19, 2021, the National Secretary of Human Rights paid homage to the victims by marking the Historic Site, inaugurating in the same act a mural made by young people from the community. The participating officials also planted a tree as part of the campaign “Plantamos Memoria” (We Plant Memory) and as a tribute to the victims of this genocide, to the former combatants of Malvinas and to the historian Juan Chico. In the same act, Capitanich announced that the provincial State would act as plaintiff in the case of the massacre.

In September 2021, the federal judge of Resistencia Zunilda Niremperger decided to enable the realization of a Trial for the Truth in relation to the events that took place, the first process of this type in which the Argentine State had to answer for its responsibility in the commission of crimes against humanity against the populations of the Qom and Mocoit ethnic groups.

In May of the following year, the federal justice of Chaco considered that the events that took place in Napalpí on July 19, 1924 were crimes against humanity committed as part of a genocide of the native peoples, and the National State joined the request for pardon made by the province of Chaco in 2008. The crimes of aggravated homicide and reduction to servitude of between 400 and 500 members of the Qom and Mocoit communities were declared proven, and reparation measures were ordered for the benefit of the communities. Among them, the judge ordered the continuity of the work of the EAAF in the search and exhumation of mass graves and urged the National Congress to establish July 19 as the National Day of Commemoration of the Napalpí Massacre. It also urged the National State to carry out a public act of recognition of its responsibility with the participation of the victims and the constitution of a museum and site of memory in the place of the events, recognizing some measures of reparation such as the apology to the native peoples made by the Government of Chaco in 2008 and the marking made in 2021 by the National Secretariat of Human Rights of the Napalpí Memorial Historic Site.

Links of interest

(Es) EAAF - Investigación de la Masacre de Napalpí

(Es) Juicio por la verdad de la Masacre de Napalpí - Argentina.gob.ar

(Es) La Masacre de Napalpí podría ser juzgada como delito de lesa humanidad - InfoJus

(Es) Napalpí, la sentencia - Revista Haroldo

(Es) Chaco inauguró monumento a víctimas de masacre de Napalpí - Ámbito

(Es) La masacre de Napalpí, una matanza que cumple 93 años de impunidad - InfoBae

(Es) Napalpí: encuentran los primeros restos óseos en la que sería una fosa común - Diario Norte

(Es) Chaco pidió perdón por una masacre de aborígenes - Clarín

(Es) Tras 97 años, habilitan realización de Juicio por la Verdad sobre la Masacre de Napalpí - Télam

(Es) Recordar Napalpí: a 95 años de la masacre - Diario Norte

(Es) Masacre de Napalpí, Argentina - Comisión Nacional de los Derechos Humanos | México